Algerian Women Writers

Monday, 2 August 2021

Djamila Debeche - Leila, A Young Girl from Algeria (novel)

Sunday, 1 August 2021

Zeinab Laouedj - The Palm Tree (poem)

Algerian poet Zeinab Laouedj was born in 1954, in Maghnia (Tlemcen). She writes in Arabic and is translated in French (all be it seldom). I have not found her translated in English.

In the above collection, you can find her poem 'Le Palmier' [The Palm Tree] dedicated to Abdelkader Alloua, the Algerian playwright assassinated on 10 March 1994, and to the poet Youcef Sebti assassinated on 27 December 1993:

"Mon pays

|

My country

|

Je suis un Lion

|

I am a Lion

|

Et je vous ferai trembler

|

And I will make you tremble

|

Jusque dans vos forêts

|

Up til your forests

|

Moi le Fou

|

Me, the Crazed

|

Fou par amour de sa patrie

|

Mad for the love of his land

|

Où nul fou

|

Where no other madman

|

Ne me ressemble

|

Resembles me

|

Ma

|

My

|

Stature

|

Stature

|

Est grande

|

Stands tall

|

Votre

|

Your

|

Tombe

|

Grave

|

Ne peut

|

Cannot

|

La contenir ...

|

Contain it…

|

La terre tourne

|

The earth turns

|

Même allongé

|

Even lying

|

Je

|

I

|

Suis

|

|

Dressé

|

Rise

|

Tel

|

Like

|

Un

|

A

|

Palmier

|

Palmtree

|

Dans

|

In

|

L'humus

|

The soil

|

De la terre."

|

Of the earth.

|

Zineb

Laouedj

|

(Eng. trans. by Nadia Ghanem)

|

Zeinab Laouedj is married to Algerian novelist Waciny Laredj. If you are in Algiers, you can find her poetry collections in the Librairie du Tiers-Monde (at the very bottom of the "Algerian Lit in Arabic" section, at the very back of the "poetry in Algerian" section , above the dust).

Saturday, 31 July 2021

Zoulikha Saoudi - An Anthology

|

| Zoulikha Saoudi 20 December 1943 - 22 November 1972 |

I was searching through Banipal's archive when I found their special issue on Algerian literature (magazine no. 7 published in 2000), a beautiful volume illustrated by the visual artist Rachid Koraichi (excuse the library sticker).

The section dedicated to Algerian literature is introduced by Waciny Laaredj whose opening piece titled "Breaking the silence on Algerian literature" pays tribute to Zoulikha Saoudi, calling her "the greatest Algerian writer in Arabic". Laaredj deplores that Zoulikha Saoudi has been entirely forgotten from the Algerian literary canon, and that instead of talking about 'the father of the Algerian novel in Arabic', we should all be discussing 'the mother of the Algerian novel'.

I'm ashamed to say that until reading Laaredj's article, I had not heard of this writer, and upon searching for more information I found several more pieces published in the Algerian press, by Waciny Laaredj who describes Saoudi's journey as a writer.

Zoulikha Saoudi was born on 20 December 1943 in Khenchela (Babar), and passed away on 22 November 1972 in Algiers, during a hospitalisation to help a difficult pregnancy. She wrote many short stories, plays, poetry, and a novel (1963). Laaredj says that the style and theme of her novel were pioneering and opened a new era, not only in Algerian fiction, but also for Algerian female novelists.

Zoulikha Saoudi's work was not published in book format. She read many of her stories on the radio to her audience under the pseudonym 'Amal' (she was also a radio journalist), and much of her work was published in newspapers, and serialised.

In his 2006 article in El Watan newspaper, Laaredj mentions that her first short story was titled 'The Victim' "written in 1960 and aired on the radio with the help of her dear friend, the poet Sayehi El Kabir". She then began to publish in the newspaper El Ahrar, as well as in El Djazaïria and El Fadjr. Her novella 'Arjouna' (We hoped) was published in the first issue of a magazine called 'Amal'. Her first novel, 'Al-Dhawaban' (The dissolution) was published as a series in the newspaper El-Ahrar (no. 24) from 11 February 1963. Laaredj describes it as a biographical novel inspired by the life of her brother who loved theatre (he was murdered soon after independence). The novel recounts the story of a man who goes to Cairo, attracted to the theatre scene there, and it describes his encounter with the city and with his theatre idols, such as Youcef Wahbi.

In that same article, Laaredj mentions that Saoudi's collection called "Ahlam el-rabi3" (Spring Dreams) and her correspondence were gathered by the Algerian poet Zaynab Laouedj (his wife), with the help of Sayehi El Kabir, Mohammed Lazrak, and Saoudi's family. I was told by Zaynab Laouedj in a private communication that she hopes to publish the gathered work in a volume soon (post 2019).

The task of collecting Zoulikha Saoudi's work was also undertaken by the scholar Ahmed Cheribet. The material he collected - short stories, letters, plays, poetry, articles, was published in 2001 in an anthology titled:

الآثار الأدبية الكاملة للأديبة الجزائرية، زليخا السعودي، 1943-1972

This book is very hard to find, and I would not have had access to it had it not been shared with me as a pdf (thank you Kamil). Since it is so rare, I share it here. Download and enjoy!

This post was comes from my other blog: TellemChahoMachaho

Friday, 30 July 2021

Baya Mahieddine - Le Grand Zoiseau (a Kabyle folktale)

this article was originally published on ArabLit

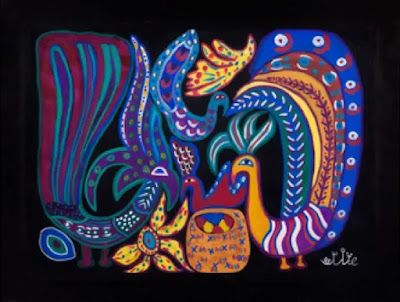

Painter and sculptor Baya Mehieddine (1931-1998), born Fatima Haddad on December 12, 1931 in Bordj el Kiffan, is best remembered as a surrealist painter and self-taught artist who marked her time (and ours) with her bold-hued depictions of women and shape-shifting animals. We know little of her as a writer. But Baya in fact wrote at least one short tale, published in the gallery leaflet of her first exhibition in November 1947.

Baya’s first exhibition was held when she was very young, sixteen years of age, at the Galerie Maeght in Paris, a gallery that still exists today. To publicize and celebrate the event, a leaflet in eight sheets was produced, and a few copies remain in circulation. The precious pages showcase eight rare lithographies by Baya, and, rarer still, a short story by her called “Le Grand Zoiseau,” which I translate here as “The Great Great Big Bird.” The wording is difficult to convey in English for though it means “the big bird” it is written phonetically in the way children pronounce “the bird” in French, mistaking the singular article with the plural. Baya also used the title “Le grand zoiseau” for one of her paintings, pictured at right.

“Le Grand Zoiseau” narrates the story of a little girl who wants to marry, and, seeing her mother deny her the right, she takes matters into her own magic hands. The world depicted here is rooted in Kabyle/Amazigh tales and mythology. It features a pet dog able to drink nearly a whole river, pots moving when they are called, talking spit, and neighbours making clever plans when stricken with the diarrhea (I have always enjoyed Kabyle stories’ uninhibited approach to bodily functions and fluids). The story is also striking in its language. It irreverently plays with the frontiers of sentences, mixing the written and the spoken, and jumbling the order of words, to rewrite the rules of what gets written while remaining perfectly enjoyable and intelligible. It is this very style that I encountered in Aziz Chouaki’s first novel, titled Baya, rhapsodie algéroise (Baya, a rhapsody from Algiers) published in 2019 by Bleu Autour editions. I had not then understood his reference nor his inspiration.

To remember them both, I am placing the story in a pot below, and letting my spit talk in the English language. The magic of my translation may not work, but yours can: others’ translations are welcome. The source can be found in the original leaflet here (PDF).

The Great Great Big Bird (Le Grand Zoiseau)

By Baya Mahieddine

Translated by Nadia Ghanem

Once, there was a little girl, and her mother was rather mean. The little girl wanted to marry, but her mother didn’t want that.

So there comes a day when a Mister comes by, and this little girl, she hides him in a hole and covers him with the djifna dish. So now, in the evening, the mother comes in and says, “Someone’s come to visit.” “Oh no, oh no, Mama, no one,” says the little girl. The mother says: “We’ll put henna on everyone in the house.” The henna is brought, and in comes the little girl, and the little dog and the cat, the chickens, the rabbits, all the animals, although not the birds, but the boxes, the tadjin, and even the water jug and the sieve and the basket.

As for the djifna, it doesn’t want to budge—the Mister’s inside. The little girl says: “The djifna’s too old, she can’t walk.” She takes a bit of henna in her hand, and she returns the djifna to its corner.

When night arrives, she asks her mother, “When is it that you’ll sleep?” The mother tells her, “When the dogs, the cats, the goats, the donkey, and all the animals scream and when the house is red, I sleep.”

The little girl lays down with her mother and she does not sleep. Then, when it’s just like this—half morning, half not-morning—she hears all the animals, and the house is all red. She gets up and she spits near her mother’s head, and near her feet, and all around. She spits by the door, and she spits outside and everywhere.

The Mister and the little girl leave together. But the pestle is on the djifna. And it begins—ding dong—to make a noise to wake up the lady.

She calls her daughter, and the spit beside her head answers, “Mummy, I’m here.” So the lady goes back to sleep, but the pestle keeps on making a noise. The mother calls out to the little girl again, and when the spit near the door and the spit outside answer, the lady knows that the girl is gone. She gets up with the little dog and sees her daughter, far, far, far.

She walks, and walks, and she arrives at the river. She can’t go over it and says to her dog: “Quick, drink all the water.” She drinks, poor ting, and her tummy’s all full. She is spent, and still there is water left. So the mother tells her daughter on the other side of the river: “Listen, if you meet animals who fight, or birds, do not separate them.” Then the mother goes back home alone. The others, they go on much further, they walk and walk.

And there, on the way: rabbits who fight, and then chickens, and dogs. The Mister wants to separate them, but the little one doesn’t want it.

A little further, they find birds fighting. There is one, blood running everywhere and nearly no feathers left. So, really then, this Mister, he goes to separate them, and the great great big bird with nearly no feathers takes the man underneath him, under his wing, and they rise up into the sky.

Then they move over the little girl, and the Mister says, “Go straight to the river, you’ll find a little girl with a crooked eye who will come to take all the water with a little dog. Go kill the little girl, and you’ll wear her skin.”

And there the bird, she goes to the river. She waits for the little girl and kills her, then she wears her skin. She takes the pot of water and walks behind the dog until the house. Getting there, she says to a lady, “Where do I put the pot?” The lady tells her, “You no longer know the habits? Place it there!”

And this little girl, there, she always was very sad in this lady’s house, because she ate with the dogs and she slept with the goats and it’s always like this, always like this.

Three days later, the great big bird comes to the roof of the house. He says to the little one, “What are you eating?” She says: “I eat with the dogs, and I sleep with the goats.” And every evening the great great big bird comes, and they always talk the same.

One evening, the neighbor has the runs. He goes out and hears the bird. Next day, he goes to a man who knows lots of things, to learn how to catch the bird, and he does as he’s told: he kills a big sheep. He hangs it outside. He takes a big branch, and all the little birds who come, he hits them with it and doesn’t let them eat. All of a sudden, there comes the great great big bird. He lets him eat, eat, eat. The bird is big and fat, he can’t fly. And the great great big bird lets go of the very very small Mister, just like that. He places him inside cotton and in a scarf. Only milk to drink, and little by little he grows. Then he says, “I am going to marry this little one.”

He gets married and tells the little girl, ”When everyone is at the door to do the drumming, I’ll let the goats go out and you, you go out to put them back in their place so that everyone sees how beautiful you are.”

So the little girl waits in the house. She is brought food and folks fall over right in the middle of the house and break all the plates and dishes seeing how beautiful she is.

All of a sudden, her husband, he lets go of the goats, and the little one goes out to put them back in their places. All the people stop the drumming and look. The brother of the groom asks, “What did you do to make your wife so beautiful like that?”

He tells him, “I put water to boil in a great big pot. I put my wife de-clothed in the basin, and I poured all the boiling water over her.”

And like that he believed! And his wife, poor thing, she died!

#

Rabia Djelti - حنين بالنعناع

Her latest novel عازب حي المرجان was published last year in 2016 again by Difaf / El-Ikhtilef.

Some of her poetry was translated into French but most such translated works are not easily available or out of stock.

Le roman de Rabia Djelti حنين بالنعناع a été co-publié par Difaf / El-Ikhtilef en 2014. Il raconte l'histoire de Dhaouia, une jeune femme qui a des ailes. Elle devient consciente qu'un sixième continent existe, et raconte son ascension vers ces nouveaux cieux.

Thursday, 29 July 2021

Amal Bouchareb - سَكرات نجمة

'Sakarat Nedjma' (Flickers of a Star) was THE thriller of 2015. Bouchareb has woven a very entertaining and daring story around the “Khamsa” (aka the Hand of Fatma), its meaning and the enigma of why it features right in the middle of our Algerian passports, in gold among the green, below the moon crescent and star, above sun rays, aside wheat and olive branches.

Ilyas Mady is found stabbed in his grandfather’s apartment in Telemly, Algiers. Mady is both Italian and Algerian, and his dual citizenship puts pressure on Inspector Ibrahim and his team to find the murderer. Ilias Mady was a world-famous artist who taught art in Turin, and had come back to Algiers at the request of Sheikh Ben Haroun to solve a puzzle. What is the origin of the Khamsa? For Sheikh Abdallah, a historian specialising in ancient secrets, it is originally a Jewish symbol, each fingers of that precious palm representing one of the books of Torah: the Exegesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Devarim. For young Ishaq, symbols don’t have a single point of origin, they come from a shared past in which members of the community have participated. When Ibrahim finds Ben Haroun’s number in the dead man’s pocket and traces Ermano Bergonzi’s calls to Turin, the net takes on an international angle and the enigma becomes deadly.

Sakarat Nedjma is Amal Bouchareb’s first novel. She published a collection of short stories last year. Bouchareb was born in Damascus. She has lived in Italy for many years.

Chapeau bas à l'excellente auteure Amel Bouchareb et son premier roman publie en 2015, le thriller سَكرات نجمة ! Si vous ne l'avez pas lu, je vous le recommande.

Djamila Debeche - Leila, A Young Girl from Algeria (novel)

Djemila Debeche (1926-2010) was born in Aïn Oulmene (Setif), Algeria, on 30 June 1926. She became early on an activist in defense of ...

-

Safia Ketou (Zohra Rabhi) is the first writer of sci-fi stories in Algerian literature. She was born in 1944 and died in 1989. Safia...

-

Rabia Djelti is mostly known as a poet but she is also a notable novelist. Her latest novel Peppermint Nostalgia (حنين بالنعناع) c...

-

Pour célébrer le 8 mars, cadeau 🎁 📚 en fin de post 🎉 😄 ! 'La Soif' est le premier roman d’Assia Djebar, publié en 19...