this article was originally published on ArabLit

Painter and sculptor Baya Mehieddine (1931-1998), born Fatima Haddad on December 12, 1931 in Bordj el Kiffan, is best remembered as a surrealist painter and self-taught artist who marked her time (and ours) with her bold-hued depictions of women and shape-shifting animals. We know little of her as a writer. But Baya in fact wrote at least one short tale, published in the gallery leaflet of her first exhibition in November 1947.

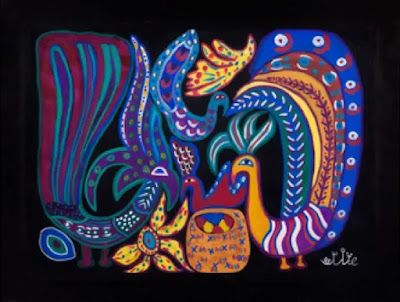

Baya’s first exhibition was held when she was very young, sixteen years of age, at the Galerie Maeght in Paris, a gallery that still exists today. To publicize and celebrate the event, a leaflet in eight sheets was produced, and a few copies remain in circulation. The precious pages showcase eight rare lithographies by Baya, and, rarer still, a short story by her called “Le Grand Zoiseau,” which I translate here as “The Great Great Big Bird.” The wording is difficult to convey in English for though it means “the big bird” it is written phonetically in the way children pronounce “the bird” in French, mistaking the singular article with the plural. Baya also used the title “Le grand zoiseau” for one of her paintings, pictured at right.

“Le Grand Zoiseau” narrates the story of a little girl who wants to marry, and, seeing her mother deny her the right, she takes matters into her own magic hands. The world depicted here is rooted in Kabyle/Amazigh tales and mythology. It features a pet dog able to drink nearly a whole river, pots moving when they are called, talking spit, and neighbours making clever plans when stricken with the diarrhea (I have always enjoyed Kabyle stories’ uninhibited approach to bodily functions and fluids). The story is also striking in its language. It irreverently plays with the frontiers of sentences, mixing the written and the spoken, and jumbling the order of words, to rewrite the rules of what gets written while remaining perfectly enjoyable and intelligible. It is this very style that I encountered in Aziz Chouaki’s first novel, titled Baya, rhapsodie algéroise (Baya, a rhapsody from Algiers) published in 2019 by Bleu Autour editions. I had not then understood his reference nor his inspiration.

To remember them both, I am placing the story in a pot below, and letting my spit talk in the English language. The magic of my translation may not work, but yours can: others’ translations are welcome. The source can be found in the original leaflet here (PDF).

The Great Great Big Bird (Le Grand Zoiseau)

By Baya Mahieddine

Translated by Nadia Ghanem

Once, there was a little girl, and her mother was rather mean. The little girl wanted to marry, but her mother didn’t want that.

So there comes a day when a Mister comes by, and this little girl, she hides him in a hole and covers him with the djifna dish. So now, in the evening, the mother comes in and says, “Someone’s come to visit.” “Oh no, oh no, Mama, no one,” says the little girl. The mother says: “We’ll put henna on everyone in the house.” The henna is brought, and in comes the little girl, and the little dog and the cat, the chickens, the rabbits, all the animals, although not the birds, but the boxes, the tadjin, and even the water jug and the sieve and the basket.

As for the djifna, it doesn’t want to budge—the Mister’s inside. The little girl says: “The djifna’s too old, she can’t walk.” She takes a bit of henna in her hand, and she returns the djifna to its corner.

When night arrives, she asks her mother, “When is it that you’ll sleep?” The mother tells her, “When the dogs, the cats, the goats, the donkey, and all the animals scream and when the house is red, I sleep.”

The little girl lays down with her mother and she does not sleep. Then, when it’s just like this—half morning, half not-morning—she hears all the animals, and the house is all red. She gets up and she spits near her mother’s head, and near her feet, and all around. She spits by the door, and she spits outside and everywhere.

The Mister and the little girl leave together. But the pestle is on the djifna. And it begins—ding dong—to make a noise to wake up the lady.

She calls her daughter, and the spit beside her head answers, “Mummy, I’m here.” So the lady goes back to sleep, but the pestle keeps on making a noise. The mother calls out to the little girl again, and when the spit near the door and the spit outside answer, the lady knows that the girl is gone. She gets up with the little dog and sees her daughter, far, far, far.

She walks, and walks, and she arrives at the river. She can’t go over it and says to her dog: “Quick, drink all the water.” She drinks, poor ting, and her tummy’s all full. She is spent, and still there is water left. So the mother tells her daughter on the other side of the river: “Listen, if you meet animals who fight, or birds, do not separate them.” Then the mother goes back home alone. The others, they go on much further, they walk and walk.

And there, on the way: rabbits who fight, and then chickens, and dogs. The Mister wants to separate them, but the little one doesn’t want it.

A little further, they find birds fighting. There is one, blood running everywhere and nearly no feathers left. So, really then, this Mister, he goes to separate them, and the great great big bird with nearly no feathers takes the man underneath him, under his wing, and they rise up into the sky.

Then they move over the little girl, and the Mister says, “Go straight to the river, you’ll find a little girl with a crooked eye who will come to take all the water with a little dog. Go kill the little girl, and you’ll wear her skin.”

And there the bird, she goes to the river. She waits for the little girl and kills her, then she wears her skin. She takes the pot of water and walks behind the dog until the house. Getting there, she says to a lady, “Where do I put the pot?” The lady tells her, “You no longer know the habits? Place it there!”

And this little girl, there, she always was very sad in this lady’s house, because she ate with the dogs and she slept with the goats and it’s always like this, always like this.

Three days later, the great big bird comes to the roof of the house. He says to the little one, “What are you eating?” She says: “I eat with the dogs, and I sleep with the goats.” And every evening the great great big bird comes, and they always talk the same.

One evening, the neighbor has the runs. He goes out and hears the bird. Next day, he goes to a man who knows lots of things, to learn how to catch the bird, and he does as he’s told: he kills a big sheep. He hangs it outside. He takes a big branch, and all the little birds who come, he hits them with it and doesn’t let them eat. All of a sudden, there comes the great great big bird. He lets him eat, eat, eat. The bird is big and fat, he can’t fly. And the great great big bird lets go of the very very small Mister, just like that. He places him inside cotton and in a scarf. Only milk to drink, and little by little he grows. Then he says, “I am going to marry this little one.”

He gets married and tells the little girl, ”When everyone is at the door to do the drumming, I’ll let the goats go out and you, you go out to put them back in their place so that everyone sees how beautiful you are.”

So the little girl waits in the house. She is brought food and folks fall over right in the middle of the house and break all the plates and dishes seeing how beautiful she is.

All of a sudden, her husband, he lets go of the goats, and the little one goes out to put them back in their places. All the people stop the drumming and look. The brother of the groom asks, “What did you do to make your wife so beautiful like that?”

He tells him, “I put water to boil in a great big pot. I put my wife de-clothed in the basin, and I poured all the boiling water over her.”

And like that he believed! And his wife, poor thing, she died!

#

No comments:

Post a Comment